|

|

|

|

Jewish World Review / May 29, 1998 / 4 Sivan, 5758

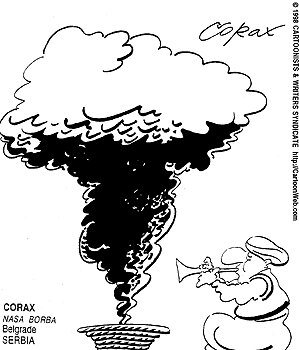

Nuclear fire and the water's edge:

American foreign policy shackled by American politics

By Josh Pollack

The self-congratulatory rhetoric of "indispensability" that accompanies high-profile American peace missions abroad, particularly in the Middle East, is truly not far off the mark. In the ongoing, on-again, off-again Israeli-Palestinian negotiations — or better yet, the triumphantly concluded Northern Ireland agreement — American facilitation has provided a crucial catalyst, perhaps even medium, for peace talks. America has become indispensable to the world, less as its policeman than as its marriage counselor.

In fulfilling at least partly a role once intended for the UN, America the Indispensable has also fired imaginations in those corners of the world where dei ex machinas remain perennially scarce. Alongside Camp David, Dayton (overlooking the roles played by American bombers and troops in securing the Dayton Accords) has become the standard metaphor for the near-omnipotence some would ascribe to the power of American diplomacy. Just as Judaism awaits the Messiah, son of David, Kosovo and Cyprus long for Richard Holbrooke.

Yet, as evidenced by recent events in the Indian subcontinent, love, peace and harmony have somehow yet to prevail worldwide. Utopian expectations for The World's Only Superpower's ability to prevent unwelcome developments are undoubtedly out of place. The chorus of recriminations against the intelligence community for its failure to detect India's preparations for nuclear weapons tests two weeks ago surely fails to give the Indians their due for cleverness and effectiveness. Nonetheless, American intervention just might have suceeded in forestalling Pakistan's counter-tests of yesterday. It failed for reasons that surely have as much to do with the problems of the United States as those of South Asia, and the consequences promise to be horrific.

Events have moved with frightening rapidity this month, and it may help to review the background. In 1947, British forces withdrew from India, which they had governed either directly or in nominally independent kingdoms. They partitioned the subcontinent into two new states: diverse but majority-Hindu India and Islamic Pakistan. As many as a million people died in the bloodletting that accompanied massive population exchanges. When the day was done, however, the Himalayan principality of Jammu and Kashmir, majority Muslim but ruled by a Hindu, remained suspended between the two emergent states, belonging to neither. As a point of ethnic tension along an unsettled border and the source of India and Pakistan's major rivers, Kashmir could not long remain up in the air.

In 1948, the same year that India's apostle of independence and peace, Mohandas K. Gandhi, was gunned down by a fanatic Hindu nationalist for his conciliatory ways, Pakistan sought to resolve the Kashmir question. The Pakistani invasion and the Indian response left Kashmir divided: one third to Pakistan, two thirds to India. The issue was refought inconclusively in 1965 and in 1971, when India reversed the outcome of a Pakistani civil war by setting up Bangladesh, the former East Pakistan, as an independent state. In these conflicts, the US 7th Fleet has never been far away from the action, the UN has issued a number of resolutions on Kashmir, and the world has generally looked on helplessly.

Elections in Jammu and Kashmir have met with minimal enthusiasm. Pro-Pakistani or pro-independence guerilla forces such as the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) have sprung up in Kashmir's Indian areas over the last ten years, only to be met with fierce counterinsurgency action by the Indian military, which generally regards the guerillas as being supported and directed from within Pakistan. Unwilling to part with strategically important terrority, India also does not wish to set any dangerous precedents for Sikh and Bodo separatists elsewhere.

Less noted but more ominous, perhaps, is the continuing, decade-long war fought directly between Indian and Pakistani troops in high passes atop the Siachen glacier, which overlooks the main road between Pakistani Kashmir and Pakistan's main ally, China. (China defeated India in a 1962 border war and is reported to have

Kashmir has now become a nuclear flashpoint. Regardless of the tendency of both sides to engage in overheated rhetoric, it is difficult to overestimate the perils of the emerging situation. India first tested a "peaceful" nuclear device — that is, an explosive with no delivery system — near the Pakistani border in 1974. In 1990, with the Soviet war in Afghanistan concluded, the Bush Administration felt safe to conclude that America's ally Pakistan, having bought, stolen and researched its way to unofficial nuclear-weapons-capable status, had triggered laws obliging the US to cut off military aid and arms sales. Like Israel, neither Pakistan nor India has acceded to the Comprehensive Test Ban or Non-Proliferation treaties.

The escalation of the nuclear arms race came with the victory of the outspokenly Hindu chauvinist Bharatiya Janata Party in India's national elections. While not the first in this decade to attempt it, the two-month old coalition government of Atal Bihari Vajpayee sought to generate popularity and reassert national pride two weeks ago by testing what he described to the world's media as a set of five nuclear warheads, ranging from a tactical nuke to a thermonuclear device — the H-bomb. Vaypayee's statements that India was merely entitled to a nuclear defense against the arsenal of recognized nuclear power China, and offering a no-first-use treaty with Pakistan, constrasted with the remarks of hardline Interior Minister Lal Krishna Advani, who last week was additionally appointed to govern Kashmir. The tests, Advani said, had "brought about a qualitatively new stage" in Indo-Pakistani relations in which India would adopt a "proactive" Kashmir strategy. He also spoke of chasing guerillas "in hot pursuit" into Pakistani Kashmir.

This combination of reasonableness and terror was played out again yesterday, but this time in Pakistan, whose government put aside the last-minute pleadings of President Clinton to test what it described as its own five warheads. "Our security, and the peace and stability of the entire region, was gravely threatened," said Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. "As any self-respecting nation, we had no choice left for us. Our hand was forced by the present Indian leadership's reckless actions. We could not ignore the magnitude of the threat."

But, Sharif noted, "These weapons are to deter aggression, whether nuclear or conventional." A government statement also added that Pakistan's new "long-range Ghauri missile is already being capped with nuclear warheads to give a befitting reply to any misadventure by the enemy." Indian Prime Minister Vajpayee, feeling the heat from the opposition in Parliament, delivered a neat self-fulfilling prophecy, declaring that Pakistan's tests had vindicated India's tests. Now rumors of impending additional Pakistani tests hint at worse things to come.

Given the whirling pace of events and the explosive nature of the Kashmir conflict, the risks are immense. Pakistan's claim that India targeted Pakistani nuclear sites before the latest tests hints at the possibility of a quick strike by one side at the other's facilities before the process of "weaponization" can be completed, or at least before very many weapons can be completed. Beyond such immediate danger, it may be some time before the weapons picture becomes clear enough for a stable deterrence to jell. And even the sort of deterrence that emerged during the Cold War may not be enough to prevent a nuclear exchange between two states with a long border, a long history of warfare, outstanding territorial issues and a mutually frustrating, ongoing conventional conflict. Think of the US' imminent invasion of Cuba in 1961, where Soviet troops waited, their tactical nuclear weapons unknown to American planners. This scenario — a day shy of nuclear war — may soon emerge as the indefinite state of Indo-Pakistani relations. Short of unforseen developments, this totally unacceptable arrangement may actually constitute the best-case scenario.

WHAT HAS THE US DONE? What more could it have done? The answers, astonishingly, are "little" and "not much." The astonishment should stem not from any lack of carrots and sticks — America is heavily endowed with both — but from the unforgiveably stupid decisionmaking process that hamstrings the executive branch's ability to react to international crises or generally to conduct constructive diplomacy: the plague of foreign policy by legislation. The damage done by Congressional grandstanding on Cuba, Libya and Iran now seems minimal compared to that done by the laws that trigger automatic sanctions against unapproved nuclear states.

America's best hope to convince Pakistan not to test lay in simultaneously punishing India while rewarding Pakistan for its forbearance and demonstrating American commitment to its conventional defense. Since the US proved unable to secure the outright cancellation of India's World Bank loans, one might have hoped that America could offer Pakistan some military assistance. But the 1976 Symington Amendment and the 1985 Pressler Amendment, triggered by Pakistan's earlier nuclear weapons development, have blocked those avenues.

The 1994 Glenn Amendment, of course, will now punish India and Pakistan equally for their nuclear tests by severing civilian aid and investment. Perversely, this rewards India for initiating the new arms race, since the sanctions can be expected to cripple Pakistan's tiny economy, while merely slowing India's down. No pre-programmed law can even begin to approximate the sense of proportion and circumstance — of situational judgment — that the effective management of foreign relations requires.

Congress has not stirred itself to act. Indeed, House Speaker Newt Gingrich is off on a trip to Israel, all the better to proclaim the line of the current Israeli government, in a classic pander to the Jewish vote — or more likely, these days, the evangelical Christian vote. Gingrich's sound bites seem designed to remind us that the old saying about politics stopping at the water's edge has long since received an indecent burial at sea. America's honest-broker status in the negotiations, it seems, is a fair price to pay for partisan advantage at home.

When legislative straitjackets constrain all diplomatic flexibility, foreign policy comes to resemble a domestic palsy. Such is the nature of the game in the Indispensible Nation

SO WHERE'S AN INDISPENSIBLE NATION when you need one?

SO WHERE'S AN INDISPENSIBLE NATION when you need one?

supplied Pakistan with missile and nuclear weapons technology.) In a grinding, essentially pointless fight that shows no signs of ending, over 10,000 men are reported to have lost their lives to shellfire, accidents, and most of all the extreme conditions at 16,000 feet above sea level and higher.

supplied Pakistan with missile and nuclear weapons technology.) In a grinding, essentially pointless fight that shows no signs of ending, over 10,000 men are reported to have lost their lives to shellfire, accidents, and most of all the extreme conditions at 16,000 feet above sea level and higher.

Josh Pollack is a contributing editor at JWR.

5/12/98: Oslo's little brother (the Copenhagen Declaration)

4/6/98: Take my alliance, please (NATO expansion)

2/22/98: Some thoughts on the eve of war (the confrontation with Iraq)

1/21/98: The dance of symbols: Bibi and Yasser in Washington

1/7/98: Iran's new opening to America

12/28/97: Arabic lessons are no substitute for Poli Sci: the dangers of the territorial fixation