|

|

Jewish World Review / May 27, 1998 / 2 Sivan, 5758

BRISK, BELARUS — Shleyma Weinstein is a dapper young man of eighty.

His generously proportioned, if somewhat bashed, twenty-year-old Renault

might not, perhaps, cut a dashing sight on the streets of Manhattan. But

in Brisk, full of Soviet-made mini-cars, people stare at it with

admiration and envy.

"I've been driving for sixty years now. I couldn't live a day without

driving. My father ran an ekspeditsya company before the war, and

I was one of his first drivers. We would take the merchandise from the

manufacturer to the retailer, and return with the retailer's payment.

People trusted us every bit as much as they would trust Reb Velvele

himself!"

Reb Velvele is the loving Yiddish diminutive of Volf ("Wolf"). The

reference is to Rabbi Yitzkhak-Volf Soloveichik (1886-1959), the last

Brisker Rav, or Chief Rabbi of Brisk. When World War II broke out, he

fled with seven of his children to Vilna, and then on to Jerusalem. His

wife and remaining four children stayed behind and were murdered. Reb

Velvele was the uncle of the famous American rabbis, Yoshe-Ber ("J.B.")

and Aaron Soloveichik.

Weinstein, who is a one-man encyclopedia of Brisk, has created a

miniature Holocaust museum in his modest flat. The moment the state

archives were opened to the public, when the Soviet Union collapsed, he

went looking, and found thousands of protokol sheets. Each is a

two-sided information sheet on every Jew in the Brisk Ghetto, containing

a photograph, a fingerprint, biographical details and some family

information.

The Nazis spared no effort to produce accurate records about every

Jewish woman, man and child that they were about to ship off to Bronaya

Gora, the mass killing site some 77 miles away, to be shot and buried in

a big pit.

"You're interested in the Soloveichiks?" Weinstein pulls out his

photocopy of the sheet for Gitala Soloveichik, Reb Velvele's fifteen-year-old daughter. The fear on the little girl's face in the photograph

is haunting.

"Who is your cousin?"

"Why, everyone in Brisk knows, Menachem Begin is my cousin. My father's

cousin Chasya — we used to call her Aunt Chasya — was Menachem's

mother. Here's her protokol sheet. She was born in Boremel,

Poland, in 1883, and murdered in Bronaya Gora, like everyone else."

When the Nazis were driven from Brisk in July 1944, fewer than ten Jews

were found. Before the war, there were 23,000 (about half the

population). Of the several hundred who live in Brisk today, all but one

came from other towns, as part of the general trend of survivor

migration to larger cities after the war.

Shleyma Weinstein is the one and only Brisk-born Jew to remain in

the city (though we did find a Brisk native, 86-year-old Sarah

Pomerantz, in Kobrin, to the east; it turns out she is Weinstein's long-lost cousin).

Shleyma's Yiddish is the very special old Brisk dialect, which is closer

to Ukrainian Yiddish than to Lithuanian, and is forged from a unique

union of the two (notwithstanding the older name of the city,

Brisk-Litovsk or Brisk d'Litta, which means "Brisk of

Lithuania"). He is, in fact, a born Yiddish dialectologist. His father

was "as Brisk as they come," but his mother was born in nearby Bereza to

the north, which was the last outpost of "pure Lithuanian Yiddish" in

these parts.

For decades, Weinstein was haunted by the vow he made when he returned

to Brisk after the war, that there would one day be a monument, with

Yiddish and Hebrew inscriptions, at the Bronaya Gora site, where some

50,000 Jews were murdered, most of them from Brisk, Kobrin, Bereza,

Antopol, Dragitshin, and Yanova. "If you live long enough," he says,

"anything can happen. One fine day we got up in the morning and the

Soviet state was gone." He saw his chance, and grabbed it.

But first he had to drive out to the killing site each day, for months,

to search out witnesses. After some of the peasants who dug the pits

agreed to testify, he obtained the official sanction for a monument.

Then came the question of money to pay for it. Without hesitation, he

gave his life savings of one thousand dollars for its construction. The

monument, which he designed, includes a picture of a railway car like

the ones used to take Begin's mother and his own mother — to the

shooting ground.

Still, Weinstein and his wife and children dream that some well-to-do

American Jews of Brisk ancestry, or some mighty organization, will one

day reimburse them, so the family can enjoy the retirement that he

worked so hard for over the decades.

Shleyma survived the Holocaust because he joined the Soviet army in May

1941, one month before the Nazi takeover. "I seem to have had a charmed

life," he muses. He was awarded eighteen medals for bravery during the

war. Decorated veterans enjoyed a cherished status in the Soviet Union.

That has survived intact in today's Belarus, the most Soviet of the

former republics. It is in sharp contrast to the attitude in some former

republics, where veterans may be thought of as "Soviet occupiers."

Weinstein often flouts traffic and parking laws to provoke a policeman

into confronting him. When he produces his papers, identifying him as a

war hero wounded in action, the policeman invariably shakes his hand and

wishes him well. During Soviet times, when any modification of a local

government decree was a feat, he pulled off many a feat. When, in the

1960s, the city council had ordered a building to be erected on the site

on Koybeshov Street where several thousand Jews had been shot, he went

into action. He couldn't stop the building order, but he did persuade

the authorities to exhume the remains of the victims. "For some reason,

the bodies had barely decomposed and many were recognizable. They were

all moved to the central Brisk cemetery."

"Why not to the Jewish cemetery?"

"Come with me," he says.

He drives me to a row of neat looking houses with large front yards.

With no hesitation, he opens the front gate of each and ushers me into

one private yard after another. The paving stones of the front patios

all along the street are old Jewish gravestones with the Hebrew

inscriptions starkly visible. In one yard, children play the local

variety of "skelley," with numbered boxes marked out in chalk upon the

gravestones. In another, a dog is doing its thing.

I grow apprehensive as one resident after another comes out to stare.

"Don't worry," Shleyme assures me. "They are scared to death of me and

they won't say a word."

They didn't.

"That is all that is left of the great old cemetery of Brisk. The

cemetery itself was turned into the sports stadium called "Lokomotiv."

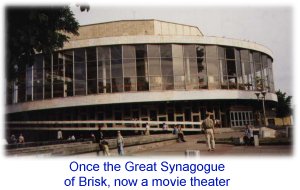

"Now come," Shleyma says, and I'll take you to our old synagogue. Di

groyseh shul [The Great Synagogue], we used to call it before the

war." We drive to a large, modern circular glass building. It is the

central movie house of Brisk.

"So where is the synagogue?"

Shleyma smiles a sad, wistful smile, and tells me to look at the top,

Our entry here is not as straightforward as it was to the gravestoned

patios. The lady in the box office tells us to "please leave" but

Shleyma points to me and tells her without blinking, that a foreign

professor of architecture, who has friends in high places in Minsk, has

come to study this masterpiece of a cinema. I bite my lip and look at

the floor, but we do get to walk around the magnificent stone walls,

which have, after all, been protected from the elements by the circle of

glass.

WHAT DRIVES Shleyma Weinstein?

"Did you know that it wasn't the famous Lithuanian Grand Duke Vitold

(1350-1430) who first invited Jews to Brisk? It was his father! His

father, Grand Duke Kieystut, back in the fourteenth century. That's how

far we go back here in Brisk!

"When I came home after the war, I knew that many Jews had been killed.

But that it could be everybody never occurred to me. Not only my father

and my mother, and my three sisters and two brothers, but everybody I

knew. I came back and I recognized the local cats, the local dogs and

the stones on the street. But not a single Jew."

Shleyma pulls out the protokol sheets for his own family. His

mother Esther, who signed the sheet in Yiddish (as did Begin's mother),

was born in nearby Bereza in 1895.

This man of steel, whose voice will not quiver, and whose eyes have long

ago finished their crying, pauses in a long silence when he comes to the

sheet for his father, Osher Weinstein, who was born in Brisk in 1873. It

also lists Shleyma's thirteen-year-old sister Golda. But instead of the

usual fingerprint, his sister, soon to be sent to Boronaya Gora,

produced an entire handprint.

"You see, she didn't understand what a fingerprint is and she dipped her

entire hand onto the inkpad and then onto the paper."

Is there any organized Jewish life in Brisk today?

Well, Shleyma Weinstein teaches a Hebrew class. He taught a Yiddish

class which he will revive as soon as books and teaching materials are

sent from abroad. He conducts the services on the holidays in a building

that housed one of the smaller synagogues before the war (he persuaded

the authorities to return it to the Jewish community). He visits the

poor Jews in town and tries to keep their spirits up.

Does he have any hobbies? "Of course, who doesn't have a hobby?" he

retorts, with his deadpan voice. "I ride up and down the city in my

Renault looking for newly exposed traces of Jewish life here."

"What could possibly be newly exposed?"

"Let's go," says Shleyma, and we do. We arrive at the corner of the

narrow street that was known as Peretz Street before the war, after the

classic Yiddish author, Y.L. Peretz. It is now called "17th of

September Street," after the date, in 1939, when the Soviets captured

western Belorussia from Poland.

Shleyma explains the kind of discoveries he has in mind. "Whenever a

building gets renovated, the first thing they do is scrape away the

standard Soviet plaster. Sometimes, it uncovers Yiddish letters from

before the war.

"Here, look!" he points with excitement. From under the plaster,

which is in the process of being removed, there peers out a pre-war

sign, painted right on to the brickwork, in Polish and Yiddish. It

advertises Ch. Greenstein's textile shop. "I remember him well, old

Greenstein."

Shleyma Weinstein growls a grunt of delight at his discovery, and says,

"wait and see, there will be more."

"By the way," he says, "I exercise for two hours each morning to keep

fit and healthy. I have to stay fit and healthy. Who else will keep

Jewish life going here in Brisk,

A half-century ago, Brisk was one of the capitals of the Torah world.

Today the scholarship that brought the village fame the world over has

been transplanted to Jerusalem, where entering the Brisker rabbinical

seminaries — plural — is no easier than gaining acceptance, say, to

Harvard. Though a shadow of its glorious self, Brisk, the village, is

still full of stories and colorful characters, as JWR's roving reporter

Dovid Katz found out.

Return to Brisk

Return to Brisk

Right underneath is the one for Hendel Soloveichik, the

rabbi's wife. It says that she was born in Shedlitz in 1894. She looks a

powerful and resolute woman. "You've heard of my cousin, of course?"

Right underneath is the one for Hendel Soloveichik, the

rabbi's wife. It says that she was born in Shedlitz in 1894. She looks a

powerful and resolute woman. "You've heard of my cousin, of course?"

where a six-sided stone structure emerges from within the glass circle.

"They thought they were being clever. The so-called architect put a

glass circle around our six-sided stone shul, and presto, there was his

movie house. That was back in 1959. Let's go inside."

where a six-sided stone structure emerges from within the glass circle.

"They thought they were being clever. The so-called architect put a

glass circle around our six-sided stone shul, and presto, there was his

movie house. That was back in 1959. Let's go inside."

New JWR contributor Dovid Katz, a former professor of Yiddish at Oxford University, is searching out Jewish life in Eastern Europe today.