Then there was the graduation 37 years ago, from Bryn Mawr College, a day soaked in rain and memories of strange but lovely traditions like step sings and lanterns and hoop races, maypole dances and then, finally, forever goodbyes.

And before that, the graduation that will remain with me until memories fade into the ether of age and forgetfulness, the only one that my father was able to attend because it happened two years before he died, the only one that I keep pictures of in my scrapbook: Merion Mercy Academy, Class of 1979.

Why am I telling you about my three graduations, these personal markers of a relatively unexceptional life?

I think that I felt obligated to write about my own experiences in order to remind you of what matters, what you yourself might have overlooked in this maelstrom of a pandemic, of death and job loss and fear of the other:

The weighty, immeasurable value of memory.

I am the sum total of every experience I've ever had, the good and the bad, but the former has outweighed the latter tenfold in my life. Those three graduations were the punctuation points, the celebratory summing up of three great chunks of living.

High school graduation marked the end of my girlhood and launched me into an uncertain young adulthood. College graduation was the cautionary message that the time for soaking up learning simply for the love of it, and without and higher purpose, was over. And law school graduation, fulfilling and exhilarating as it was, signaled the fleeting passage of time, and the need to finally, seriously, begin that career I'd dreamed of as a little girl who watched "To Kill A Mockingbird" until the VHS tape broke.

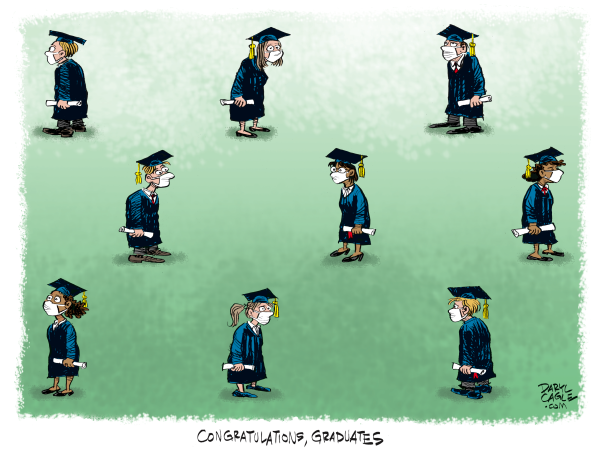

I wager that for you, these communal moments of achievement, celebration and passage are as important. And that's why we need to step back a bit, a few feet, choose a vantage point from a safe and objective distance, and try to comprehend the magnitude of loss being felt by students who will not have these markers, these celebrations, these rites of passage.

It's all well and good to emphasize the public welfare and how we need to social distance and wear this mask or those gloves, and call the authorities if we see our neighbors doing things that violate the rules, and feel so virtuous that we are doing our best to flatten the curve, wrestle it to the ground, and create that "new normal" that is so important to our sense of stopping the plague. I sometimes ridicule the extremes we've gone to in our attempts at mitigation, but I understand the need to be cautious.

And yet, I cannot escape this feeling that we are ignoring the very real, very human pain felt by those whose memories are being erased before they can be formed, a pre-emptive Etch-A-Sketch.

I know of parents who grieve the losses that their high school seniors are enduring, no proms, no award ceremonies, no parties with decorations in blue and gold, crimson and gray, white and emerald. No pictures of mortarboards filling the air like seagulls sailing toward an endless future. No poses at the beach (some of which would have been inappropriate for family consumption, but whatever).

No laughter, except from a 6-foot distance, with the windows up.

I want us to feel, deeply, the losses that are accumulating for the Class of 2020, and as we put on our masks, to acknowledge that while we were worried about the future, we were erasing other people's pasts. It was, perhaps, necessary.

But we owe these kids, and their parents and loved ones, the grace of acknowledging what we stole from them in our utilitarian quest for survival.

And we don't get to say "but it was all for the best." Because for some of them, it wasn't. And if I'd lost the opportunity to make the memories that fill the recesses of my resting mind, it wouldn't be for me, either.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Christine M. Flowers is a lawyer and columnist.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author