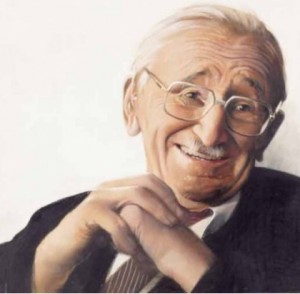

Nobel Prize-winning economist Friedrich Hayek.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Friedrich Hayek.

In 1974, Nobel Prize-winning economist Friedrich Hayek criticized those who believed they could measure the real-world impact of economic theories with scientific precision. They were wrong, Hayek said in his Nobel lecture, entitled "The Pretence of Knowledge." They didn't have enough solid information. What they lacked couldn't be reduced to a number. It wasn't quantifiable. Yet economists continued to "proceed on the fiction that the factors which they can measure are the only ones that are relevant."

It might seem a stretch, but Hayek's insight applies to politics, and notably to the 2016 presidential campaign. Reporters and commentators have been jumping to conclusions based on insufficient evidence, particularly in the Republican race. This is less true of the Democratic contest, with its smaller field of candidates and less persistent media coverage.

At the moment, there's nothing going on in either party's campaign that is predictive of what will occur when we get to the Iowa caucuses (February 1) and New Hampshire primary (February 9). This is not a historic first. Wildly off-base projections are the norm in the nomination races. Recall the situation at roughly this time in 2007. The eventual GOP nominee, John McCain, was dead in the water. Barack Obama barely registered a blip.

The lesson here has largely gone unlearned. We see campaign stories about the threat Wisconsin governor Scott Walker poses to Jeb Bush in the New Hampshire primary next year, based on a fleeting poll. And considerable attention has been paid to New Jersey governor Chris Christie's "comeback." What comeback? He hasn't even announced he's running, much less competed with his rivals in a televised debate. The first debate isn't until August 15.

At this stage, polls that rank the candidates are dubious but ubiquitous. National polls are totally irrelevant. They are unconnected to how candidates might do in early caucuses (Iowa, Nevada) or primaries (New Hampshire, South Carolina). In fact, state polls aren't much help either.

Such polls should be taken "with whole tablespoons full of salt," according to stats geek Nate Silver. "And it's probably best to look at the favorability ratings of each candidate rather than head-to-head polls, since favorability polls allow voters to say they don't know enough about the candidates to have formulated an opinion."

This far from the first actual voting—nine months—head-to-head polls tend to favor candidates with high name ID, like Hillary Clinton. These polls are not quite worthless, but close to it.

Pollster Frank Luntz says favorability is important because it points to a candidate's potential. It shows whether a candidate has "room to grow." And from that, "we know what their floor is .??.??. and what the ceiling is." But not much more.

Favorability has the advantage of being less volatile than head-to-head matchups. Among Republicans, the lead changes almost weekly in polls of voter preference. Should the press play up a candidate for a day or two, as happened after an Iowa speech by Walker and with Florida senator Marco Rubio's formal entry into the race, who's ahead can change overnight. Bush, Walker, and Rubio have each come in first in at least one

poll recently.

Luntz limits his surveys to the initial four contests and asks Republican voters only about candidates with name recognition of 30 percent or better. The key result is the "net positive." That's the difference between positive and negative responses when voters are asked about their view of a candidate.

With a high net positive, a candidate has an opportunity to build his support, Luntz says. In his recent surveys, Walker and Rubio scored net positives of nearly 50 percent. Louisiana governor Bobby Jindal was 20 percent positive.

Christie hovered just above zero in net positive. "That's a bad position to be in," Luntz says. But Christie can recover with a strong performance in the Republican debates, the pollster says. We'll see.

Focus groups—normally a dozen or so voters—are a specialty of Luntz. He did two in New Hampshire in mid-April and came away with one strong conclusion: GOP voters prefer a governor to a senator as their presidential candidate.

What about money? It matters.

Fundraising is rightly seen as a proxy for what Silver calls "a candidate's organizational strength." In the 2012 race, Mitt Romney spent lavishly in the Florida primary to defeat Newt Gingrich, who was unable to blunt Romney's expensive wave of TV ads. The Florida victory all but sealed the nomination for Romney.

But money isn't everything. In 2016, as many as a half-dozen Republican candidates are likely to have enough money to compete in every early state. And as successful as Jeb Bush was in his early fundraising, it wasn't sufficient to encourage any candidates to drop out.

So where does all this leave us? Nationwide polls tell us little about individual states, where nominations are decided. And states differ politically. Religious Iowans and secular New Hampshire Republicans don't match. Nor do GOP voters from Nevada and South Carolina. State polls aren't predictive the April before election year. Hard facts and reliable numbers are few.

In his famous speech, Hayek used a sports analogy. "Consider some ball game played by a few people of approximately equal skill," he said. If we knew specific information about each player, "such as their state of attention, their perceptions and the state of their hearts, lungs, muscles, etc. at each moment of the game, we could probably predict the outcome." Political campaigns, at least in their early stages, are similar. We can't predict their outcome either.

Comment by clicking here.

Fred Barnes is Executive Editor at the Weekly Standard.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author